Some comprehensive analysis required.

There is far more to complex exchange systems in New Guinea than pottery alone. A host of ‘intangibles’ for starters.

Some comprehensive analysis required.

There is far more to complex exchange systems in New Guinea than pottery alone. A host of ‘intangibles’ for starters.

From ‘The Conversation’. Authors Tristan Salles, Ian Moffat, Laurent Husson, Manon Lorcery, Renaud Joannes-Boyau.

Aboriginal people made pottery and sailed to distant offshore islands thousands of years before Europeans arrived

Article from The Conversation by Sean Ulm, Ian J McNiven and Kenneth McLean

Duane Hamacher, The University of Melbourne; Greg Lehman, University of Tasmania; Patrick D. Nunn, University of the Sunshine Coast, and Rebe Taylor, University of Tasmania

Content note: this article mentions genocide and acts of colonial violence against Aboriginal people.

How long do you think stories can be passed down, generation to generation?

Hundreds of years? Thousands?

Today, we publish new research in the Journal of Archaeological Science demonstrating that traditional stories from Tasmania have been passed down for more than 12,000 years. And we use multiple lines of evidence to show it.

Within months of establishing a colonial outpost on the island in 1803, British officials had committed several acts of genocide against Aboriginal Tasmanian (Palawa) people. By the mid-1820s, soldiers, convicts, and free settlers had taken up arms to fight what became known as the “Black War”, aimed at capturing or killing Palawa and dispossessing them of their Country.

Tasmania’s colonial government appointed George Augustus Robinson to “conciliate” with the Palawa. From 1829 to 1835, Robinson travelled with a small group of Palawa, including Trukanini and her husband, Wurati. By 1832, Robinson’s “friendly mission” had turned to forced removals.

Robinson kept a daily journal, which included records of Palawa languages and traditions. Over time, Palawa men and women slowly began to share some of their knowledge, explaining how their ancestors came to Tasmania (Lutruwita) by land from the far north, before the sea formed and turned their home into an island. They also spoke about the Sun-man, the Moon-woman, and a bright southern star.

These stories are of immense importance to today’s Palawa families who survived the devastating impact of colonisation, and who continue to share these unique creation stories. Through careful investigation of colonial records, and collaborating with Palawa knowledge-holders, we found something remarkable.

Over the past 65,000 years, Australia’s First Peoples witnessed natural disasters and significant changes to the land, sea and sky. Volcanoes spewed fire, earthquakes shook the land, tsunamis inundated the coastlines, droughts plagued the continent, meteorites fell to the earth, and the stars shifted in the night sky.

Some 20,000 years ago, the world was in the grip of an ice age. Australia was conspicuously drier than it is today, and the ocean was significantly lower. All of that sea water was bound up in glaciers that swathed vast tracts of land, particularly across the Northern Hemisphere, and polar ice caps much larger than ours today.

As time passed, temperatures gradually rose and the ice began to melt. After 10,000 years, the sea level had risen 125 metres; a process that dramatically transformed coastlines and submerged landscapes that had been ancestral Country for thousands of generations. This forced humans to change where and how they lived.

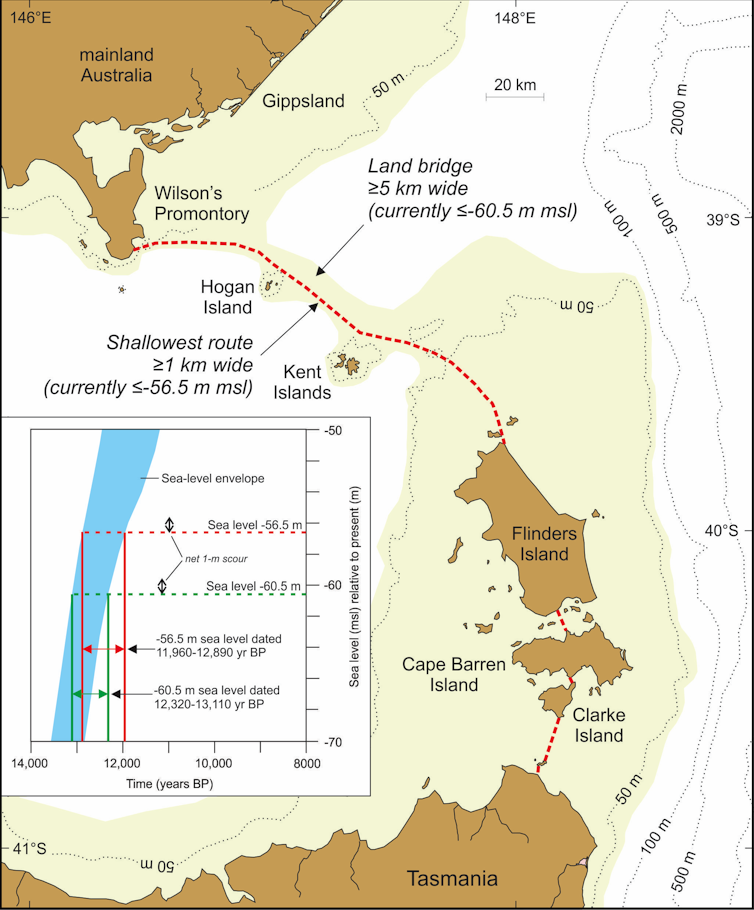

During the ice age, both Lutruwita and Papua New Guinea were connected to mainland Australia by dry land, forming a landmass called Sahul. As the seas rose, Tasmania’s connection gradually narrowed to form what geologists call the Bassian Land Bridge.

People continued to live on this “land bridge”, but by 12,700 years ago it had narrowed to just 5 kilometres wide (lime-green shading on the map above). Habitable land was gradually reduced as the sea closed in. Less than 300 years later, the “land bridge” was gone and Lutruwita was completely surrounded by water.

Palawa traditions from that time survived hundreds of generations of retelling, forming part of a larger canon of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories around Australia. They described rising seas and submerging coastlines as the ice sheets melted before levelling off around 7,000 years ago. Stories of similar antiquity are known from other parts of the world.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures developed rich and complex knowledge systems about the stars, which are still used today. They describe the movements of the Sun, Moon, and stars, as well as rare cosmic events, such as eclipses, supernovae, and meteorite impacts.

In the 1830s, a Palawa Elder spoke about a time when the star Moinee was near the south celestial pole. He laid down a pair of spears in the sand and drew a few reference stars to triangulate its position.

Colonists seemed perplexed about the presence of an antipodean counterpart to Polaris, as no southern pole star exists today. Some tried to identify the stars on the star map, but seemed confused and labelled them incorrectly, as they were unaware of an important astronomical process called axial precession. https://www.youtube.com/embed/2JJjNc1xPKw?wmode=transparent&start=0

As the Earth rotates, it wobbles on its axis like a spinning top. This shifts the location of the celestial poles, tracing out a large circle every 26,000 years. As thousands of years pass by, the positions of the stars in the sky slowly change.

Long ago, Canopus was at its southernmost point in the sky. Lying just over 10 degrees from the south celestial pole, it appeared to always hover in the southern skies each night. That last occurred 14,000 years ago, before rising seas turned Lutruwita into an island.

We can see through independent lines of evidence that Palawa stories have been passed down for more than twelve millennia. We also find here the only example in the world of an oral tradition describing a star’s position as it would have appeared in the sky over 10,000 years ago.

Our investigation of colonial records that record traditional systems of knowledge has demonstrated a powerful cross-cultural way of better understanding deep human history. This also recognises the immense value of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander traditions today.

This research was co-authored by graduate Michelle Gantevoort from RMIT University, and student researchers Ka Hei Andrew Law from the University of Melbourne and Mel Miles from Swinburne University of Technology.

Duane Hamacher, Associate Professor, The University of Melbourne; Greg Lehman, Pro Vice Chancellor, Aboriginal Leadership, University of Tasmania; Patrick D. Nunn, Professor of Geography, School of Law and Society, University of the Sunshine Coast, and Rebe Taylor, Associate Professor of History, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

In this piece of work i write about developing a healing Sahulian perspective when conceptual craftspeople fashion representations of First Peoples. Peoples-and-countries are one.

There needs to be representational justice for First Peoples to ensure an adequate definition of their realities. According i reject the idea that agriculture, as commonly understood, provides the only privileged base from which we can interpret our human story.

I argue here that First Peoples in ‘Australia’ did not move to agriculture as they remain in good faith with an ‘eternal life design’. Moving to horticulture would result in a lower level of Being.

Co-existing forms of knowledge are required in respect to the ‘science’ – ‘traditional knowledge’ debate.

This is especially import so proper understanding of First Peoples Ways can assist in the vital task of moving from a ‘hot’ society’ to, as least, a cooler one by learning from indigenous sources.

The issue of what happened in New Guinea, as part of Sahul, requires another chapter.

Bruce Reyburn – Coledale NSW

If the link does not work for you contact me at sahulman@sahul.online and i’ll get something which does.

Adams S, Norman K, Kemp J, Jacobs Z, Costelloe M, Fairbairn A, Robins R, Stock E, Moss P, Smith T, Love S, Manne T, Lowe K, Logan I, Manoel M, McFadden K, Burns D, Falkiner Z, Clarkson C

Preprint from Research Square, 25 Apr 2023

DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2843483/v1 PPR: PPR650347

Sahul (the supercontinent formed by New Guinea and Australia at times of lower sea level) was peopled by 65,000 ± 5,700 years ago, but secure archaeological evidence for occupation before ~25,000 years ago on the eastern seaboard of Australia has proven elusive. This has prompted some researchers to argue that the coastal margins remained uninhabited prior to 25 ka. Here we show evidence for human occupation beginning between 30 ± 6 and 49 ± 8 ka at Wallen Wallen Creek (WWC), and at Middle Canalpin Creek (MCA20) between 38 ± 8 and 41 ± 8 ka. Both sites are located on the western side of Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island), the second largest sand island in the world, isolated by rising sea levels in the early Holocene. The earliest occupation phase at both sites consists of charcoal and heavily retouched stone artefacts made from exotic raw materials. Heat-treatment of imported silcrete artefacts first appeared in sediment dated to ~30,000 years ago, making these amongst Australia’s oldest dated heat-treated artefacts. An early human presence on Minjerribah is further suggested by palaeoenvironmental records of anthropogenic burning beginning by 45,000 years ago. These new chronologies from sites on a remnant portion of the continental margin confirm early human occupation along Sahul’s now-drowned eastern continental shelf.

Huettmann, F. (2023). In Bed with a Big Bad Neighbor for Life: The Middle Power of Australia as a Domestic, Cultural, Political, Material and Environmental Sustainability Problem for Papua New Guinea and Beyond?.

In: Globalization and Papua New Guinea: Ancient Wilderness, Paradise, Introduced Terror and Hell. Springer, Cham.

Looking at the big floods in the Gulf Country at this time brings to mind the lake which once occupied part of Sahul now under sea water.

“The Gulf and adjacent Sahul Shelf were dry land at the peak of the last ice age 18,000 years ago when global sea level was around 120 m (390 ft) below its present position. At that time a large, shallow lake occupied the centre of what is now the Gulf.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulf_of_Carpentaria (accessed 14 March 2023.

See map from Nature Communications (copyright restrictions – and note source article) https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map-of-Sahul-Australia-and-New-Guinea-showing-the-distribution-of-reliably-dated_fig1_341454456

Does this lake have a name?

Yes – Lake Carpenteria

“When sea level began to rise after about 12,000 BP, it began having an effect on the lake, a permanent open connection to the sea forming, though between about 12,000 to 8,000 BP it apparently remained as a low salinity water body, partly because the Arafura sill allowed only limited exchange with the ocean, and partly because of the monsoonal conditions with tropical cyclones dumping large amounts of rain on the catchments that drained into the lake. The present Torres Strait was formed as the land bridge between the Australian mainland and the previously connected New Guinea was completely flooded, after which the lake was swamped by the rising sea. Unlike many Australian lakes, Lake Carpentaria never became a dry playa at any time throughout its existence.” M. H. Monroe https://austhrutime.com/lake_carpentaria.htm

The First Australians grew to a population of millions, much more than previous estimates

Corey J. A. Bradshaw; Alan N Williams; Frédérik Saltré, Kasih Norman; Sean Ulm

https://theconversation.com/the-first-australians-grew-to-a-population-of-millions-much-more-than-previous-estimates-142371 – accessed 30 Jan 2023